The Evacuation of Dunkirk

Where is Dunkirk?

Dunkirk (French: Dunkerque) is a small town on the coast of northern France. It is the northernmost city in France, lying about 6.2 miles from the Belgian border and was the scene of a massive military campaign during World War Two. The Dunkirk 1940 Museum documents Operation Dynamo, the WWII evacuation of Allied soldiers from the city's beaches.

Allied forces stuck in Flanders

The so-called “phoney war” was over on May 10th, 1940 when Nazi Germany invaded Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. What had appeared to be solid Allied lines of defence had been breached without opposition by the sheer speed and violence of the German Blitzkrieg (German for “lightning war”) tactics.

In the face of such a highly mobile ground forces supported by panzer tanks along with superior air power and a coordinated strategy, all three countries would succumb quickly. The Allies, instead of looking across the front line to face the enemy, had been shocked to discover German tanks behind them. Confusion reigned among the B.E.F and French Armies and the enemy was closing fast around Dunkirk.

General John Gort, V.C., D.S.O and two bars and commander of the British Expeditionary Force (B.E.F) had no choice but to remove his men by sea. Previously laid plans for a mass evacuation were already underway, and Gort was already making a tactical withdrawal to the site which offered the best long, open beaches at the closest point of England.

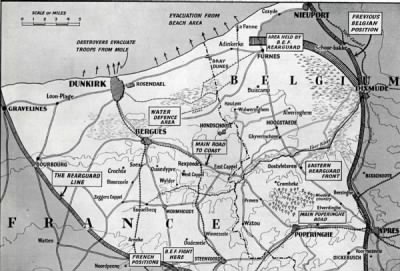

(Map showing the successful rearguard action and evacuation from Dunkirk and the surrounding beaches - ForcesWarRecords Archive)

The Withdrawal from Dunkirk

The evacuation of Dunkirk, which has been called the ‘miracle of deliverance by Winston Churchill, was nothing if not epic. As Robert Jackson describes in his ‘Dunkirk: the British Evacuation, 1940’, the battle raged inland, on the beaches, across the sky and into the sea, with all hands working to the absolute limits of their endurance to ensure that as many men as possible were carried away from danger and returned across the Channel to British shores. For the 366,131 men saved, 226 British and a further 168 Allied ships out of 683 were sunk, 177 aeroplanes were destroyed or damaged, including 106 fighters, and 68,111 men of the B.E.F. were killed or captured, with a further 40,000 French troops being taken prisoner. ‘Operation Dynamo’ was far from small.

Oddly, preparations for the evacuation began as early as 14th May 1940, as an order was broadcast at 9am that day, requiring all owners of ‘self-propelled pleasure craft between 30-100 feet in length’ to register their boats with the Admiralty within 14 days. The strange part is it was not, at this juncture, thought very likely that an evacuation would be needed, and nobody is quite sure who anticipated this possibility and set the wheels in motion. Anyway, by the time the small boats were needed they had already been logged and a register compiled, with the owners ready to spring into action when called.

The first wave of uneasiness didn’t hit the admiralty until 19th May. The German troops and Panzers were rapidly pushing through the Ardennes into France, and Vice Admiral Bertram Ramsey, based at Dover castle, was given the job of brainstorming how an evacuation would be actioned in case of need, with the aim being to remove 10,000 men per day from each of Calais, Boulogne and Dunkirk (in the end only Dunkirk was used). The next day Churchill suggested amassing small ships for just such an instance, not realising the process had already begun. Small boats, of course, would be better able to cope with shallow water, avoid numerous obstacles and creep as near as possible to the beach, acting as a ferry service to run troops to larger destroyers and minesweepers waiting out at sea.

On 26th May things took a turn for the worse concerning the B.E.F.’s position. The Belgium army, which had been fighting gallantly alongside General Brooke’s II Corps, collapsed. A dangerous gap in the Allied defences was thereby opened, leaving just the 143rd Brigade of the 48th Division between the Germans and passage into France along the coast, where the B.E.F. was waiting. The German troops who had already entered the country circled round south of the B.E.F., 25 miles north of Paris, and the hapless Allied army found itself trapped in the centre of a pincer movement. The Ypres-Comines canal became the Front Line, as troops were dispatched to hold off the German advance down the coast at all costs. If the Germans surged forward and reached the beaches before the B.E.F., the claw would slam shut and the Allies would be crushed. It was time to evacuate while they still could; ‘Operation Dynamo’ was given the go-ahead to commence.

While everyone else hurried for the coast, General Sir Robert Forbes Adam was tasked with organising the defence of the British line, and General Franklyn was given the unenviable job, along with the 3rd, 4th, 5th and 50th Divisions, of moving to intercept, and effectively ‘hold off’, the Germans looking to advance from Ypres, while the French IV and V Corps fought alongside them at Lille. The troops fought hard for two full days, giving their comrades the time, they needed to strike out for the escape point, but were soon forced into a ‘fighting withdrawal’, destroying bridges as they went. Many men would lose their lives in this gallant endeavour, and the French units were essentially cut to ribbons before they surrendered on the 31st. Eventually the British troops, and what was left of the French army, retreated right back to surround Dunkirk, now considered the only possible route of escape, and remained to defend the perimeter. Every hour would now make a massive difference in determining how many men would ultimately make it home.

(Allied troops taking cover on a Dunkirk beach amid bursting bombs and German machine-gun fire - ForcesWarRecords Archive)

Meanwhile, the 1st, 2nd, 42nd, 44th, 46th, 48th and 1st Armoured Divisions were ordered to head to the Dunkirk beaches and embark for England. The retreating troops had mixed feelings; they were dismayed, as they had expected to stand and fight rather than to retreat, but also relieved to be ordered out of harm’s way. That order was easier for some to follow than others; General Alexander’s 1st Division, for example, faced a gruelling 55-mile march to make it to Dunkirk, with the Luftwaffe pummelling them as they went. As they hurried forward, they were painfully aware that they were last in the queue for evacuation, and might have a long wait ahead of them, if they made it off the beach at all.

(British and French troops massed on the dunes at Dunkirk in readiness to be taken aboard ships assisting in the evacuation - ForcesWarRecords Archive)

They weren’t the only ones who were worried. Captain William Tennant and the other on-the-spot organisers of the evacuation found themselves with a massive administrative headache. The sheer numbers of troops arriving at the beach all at once – which, while very long, was only a mile wide – meant that the men were forced to spread out further and further away from those in command, making it difficult to transmit orders, and the Germans had completely destroyed the nearby port. That being the case, there were only two loading points to place troops into the boats from, a jetty to the west of the beach and a mole to the east. Lots of men became separated from their units, so it was hard to know who they should listen to and where they ought to be, and the sick and stragglers had to be sorted and cleared before the organised units got a look in.

Even assuming the orders made it to the men, and they understood where they were headed, they faced a long journey over the pocked and debris-laden beach to get to the exit points, risking attack all the time from German planes that knew exactly what location they were aiming for. There was some respite from the Luftwaffe on the 30th May due to bad weather, and nights were safer, but otherwise the men were sitting ducks, especially as many had been told to destroy all weapons. The R.A.F. were there too, and working hard – apparently they flew 171 reconnaissance missions, 652 bombings and 2,739 fighter sorties – but their numbers were swallowed up by the far more numerous Luftwaffe, especially as Churchill, knowing France was lost, held back many planes that could have been sent in order to preserve them for home defence. Twice as many men remained to be evacuated as had been originally thought, and the waiting crowd continued to swell. Eventually the organisers, in sheer desperation, created a third jetty out of trucks parked deeper and deeper into the surf to speed the loading into small ships. The captains of those ships risked their lives time and again, running the gauntlet of bombs and obstacles to reach the beach, then risking being capsized or sunk by the frantic troops and heavy equipment.

The waiting troops suffered keenly from hunger and thirst, no rations having been provided, and became less and less alert as time went by. They huddled down miserably into their self-dug foxholes, watching the destruction spread around them, and prayed for it all to be over. ‘Dunkirk: the British Evacuation, 1940’ quotes Sergeant A. Bruce, 7th Field Company Royal Engineers, as saying, “Men were lying there in grotesque attitudes of death, eyes and mouths wide open. It was hard to believe that they had ever been human beings. I could not help thinking, as I half fell, half walked through the wet sand, of the funeral those boys would have had at home, with tenderness and flowers. Yet here they lay where they had died, like dogs that had been run over in the street.”

Eventually, as the Germans advanced, the key generals were pulled back to Britain, with just General Alexander being left to cover the rear of the retreating army. The battalions holding the perimeter, too, were ordered to make haste to the beach. Some would make it before the Germans seized a bridgehead and advanced to within sight of the sand, some would not. Many of the bravest men of all, who had resisted the temptation to flee and turned their backs on the retreat routes in order to follow orders and work to protect the evacuating troops, were left behind and would endure a life of imprisonment for the remaining 5 years of the war. Others, of course, were struck down, their lifeless bodies joining those of countless comrades. When the Germans finally gained control of the beach, it was littered as far as the eye could see with dead men and broken or burned equipment, covered in potholes and smoking like the very depths of hell.

However, the operation was largely hailed to have been a success. The British commanders were able to do what Hitler never did learn to; admit when they were beaten, and take every precaution to pull their men back to safe ground, that they might live to fight another day.

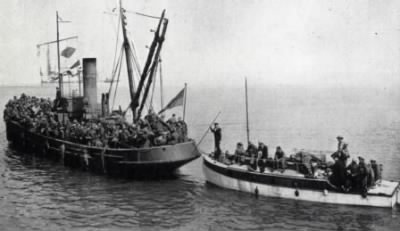

(Embarking from a jetty of lorries near Dunkirk - ForcesWarRecords Archive)

Why was it called Operation Dynamo?

It is mentioned that Admiral Bertram Ramsay directed the evacuation with his staff working in a room deep in the Dover cliffs that had once contained a dynamo – a machine that generated electricity. However, there’s no evidence for this. Dynamo was just a code word according to English Heritage.

Dunkirk Little Ships.

As soon as the veil of secrecy was lifted and news of the operation Dynamo broke at 6 pm on 31st May many boat owners simply set sail to Dunkirk. This huge civilian effort lifted 26,000+ men from the beaches, in addition to the thousands that had already been evacuated.

Today the Association of Dunkirk Little Ships keeps alive and preserves for posterity the memory and identity of those ‘Little Ships’ that went to the aid of the British Expeditionary Force in 1940 and took part in Operations Dynamo. The Association organises several meetings 'on the water' each year where the Little Ships may be seen and appreciated by the public. Every 5 years the Little Ships, supported by the Royal Navy, return under their own power to Dunkirk.

Little Ships are also entitled to display a plaque marked 'DUNKIRK 1940'.

(Dunkirk Little Ship heading for England - ForcesWarRecords Archive)

Dunkirk Stats

- 338,226 troops were evacuated from Dunkirk between 27th May & 4th June 1940

- 98,780 men were lifted from the beaches; 239,446 from the harbour at Dunkirk

- 933 ships took part in Operation Dynamo, of which 236 were lost and 61 put out of action. With French, Belgian, Dutch and Norwegian ships taking part in the operation alongside the ships of the Royal Navy

- The number of little boats that sailed on their own initiative will never be known

- 126 merchant seamen died during the evacuation

- 68,111 men of the BEF were captured or killed during Blitzkrieg, retreat and evacuation

- 40,000 French troops were taken into captivity when Dunkirk fell

- Churchill had been Prime Minister for only 16 days when the evacuation began

- The threat of invasion was so real that on 29 May Churchill proposed laying gas along the beaches of the south coast

- The BEF left the following equipment behind in France, much of it to be recycled by the German Army –

-2,472 guns

- 63,879 vehicles

- 20,548 motorcycles

(A British soldier giving a comrade a drink of hot tea on the quayside after the hazardous voyage home from Dunkirk - ForcesWarRecords Archive)

Dunkirk Memorial

The Dunkirk Memorial stands at the entrance to the British war graves sections of Dunkirk Town Cemetery, which lies on the eastern outskirts of the town on the road to Veurne in Belgium.

The names of the men commemorated are engraved on Portland stone panels on a series of columns on each side of a broad walk, forming an avenue which leads to a shrine. At the entrance to the avenue are two columns surmounted by stone urns, and bearing on the front faces the inscription, on one in French and on the other in English:

Here beside the graves of their comrades

Are commemorated the soldiers of the

British Expeditionary Forces who fell in

The campaign of 1939-1940 and have no

Known grave.

The total number of names on the memorial is 4,534; of these, 6 were members of the Royal Indian Army Service Corps, and all the others belonged to the land forces of the United Kingdom.

Their comrades of the naval and air forces and of the Merchant Navy who died during the campaign and who have no known grave are commemorated on the naval memorials in the United Kingdom, on the Air Forces memorial at Runnymede, and on the Merchant Navy memorial on Tower Hill in London.

Helping you find your WWII Dunkirk Ancestor

By far the most common problem that people researching their family trees come across is a shortage of accessible records relating to the Second World War. The Public Records Act governs which materials created by the government can be released over what timescales. The agreed policy between MOD and The National Archives is that service records will be transferred to The National Archives at the point that the majority of the subjects of the record have passed their 100th birthday as, until that point, the record relating to any one subject will be closed.

It seems likely that the records will become publicly available in the mid-2020s given that an 18 year who enlisted at the mid-point in the war would have been born around 1924. However, there are numerous exceptions which continue to restrict access, e.g. when release of records may cause damage to the country’s image, national security or foreign relations.

Records from the Second World War fall under these restrictions, as many of the men and women who served are still alive and wouldn’t want personal information disclosed. Thus, you won’t find the full record for a relative who fought in that war anywhere except with the Ministry of Defence.

Small parts of a Second World War serviceman’s record may be found, such as those listing his or her death, casualty/missing reports, capture or medals awarded. Forces War Records, for example has over 24 million World War Two records, these are made up from ‘some’ of the following collections:

WWII Daily reports (missing, dead, wounded & POWs)

- Kept under reference WO417 at the national archives these ‘daily’ reports were made on a 24/48 hour basis and often include information that can’t be sourced anywhere else!

- (SEARCH THIS COLLECTION HERE)

Bomber/Fighter Command Losses 1939-1945

- Bomber/Fighter Command Operational Losses in the European Theatre of War covering both Aircraft and Aircrew 1939-1945.

- (SEARCH THIS COLLECTION HERE)

WWI & WWII, Commonwealth War Graves Commission Death Registers

- The registers record all those who died between 4/8/14 and 31/8/1921 and between 3/9/39 and 31/12/47.

- (SEARCH THIS COLLECTION HERE)

Records of Soldiers Awards from the London Gazette

- A soldier mentioned in dispatches (or despatches) (MID) is one whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which is described the soldier's gallant or meritorious action in the face of the enemy.

- (SEARCH THIS COLLECTION HERE)

WWII, Allied Prisoners of War, 1939-1945

- Personnel of the British armed forces as well as Merchant seamen were captured during the Second World War and placed in one of the different types of prisoner of war camps run by the Germans. Oflag was a prisoner of war camp for officers, Stalag was for enlisted personnel, and there were separate camps for navy, aircrews and civilians (Marlag/MIlag, Lufts and Ilag respectively)

- (SEARCH THIS COLLECTION HERE)

Our database also includes many more collections from Rolls of honour, UK Army Lists, nominal rolls, Home Guard records, RAF, Navy collections and SO much more. Please see our full collections list HERE

Let us help you with your family history research, visit the Forces War Records website and search our wealth of records including those from World War II.